Some Cases of Fortuitous Self-Medication with Biochemically-Active ‘Wild Card’ Plant Polyphenols

A tale of chocolate, sweet potato, and bitter (tartary) buckwheat

Introduction

I encountered this passage recently:

In what sounds like dystopian sci-fi, researchers have recently shown that infusions of youthful blood can improve the health of older people. A new study has found that an existing arthritis drug can effectively rejuvenate blood stem cells, mimicking the benefits of youthful blood transfusions.

“An aging blood system, because it’s a vector for a lot of proteins, cytokines, and cells, has a lot of bad consequences for the organism,” said Emmanuelle Passegué, corresponding author of the study. “A 70-year-old with a 40-year-old blood system could have a longer healthspan, if not a longer lifespan.”

Blood cells are produced by stem cells located in the bone marrow, and the team started by exploring the environment, or “niche”, in which these stem cells exist, and how it changes during aging in mice. They found that over time, the niche deteriorates and becomes overwhelmed by inflammation, which impairs the blood stem cells.

On closer inspection, the scientists identified one particular inflammatory signal, called IL-1β, as critical to impairing the blood stem cells. And since this signal is already implicated in other inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, there are already drugs in wide use that target it.

Sure enough, the researchers used an arthritis drug called anakinra to block IL-1β in elderly mice, and found that the blood stem cells returned to a younger, healthier state. This helped improve the state of the niche, the function of the blood stem cells and the regeneration of blood cells. The treatment worked even better when the drug was administered throughout the life of the mice, not just when they were already old.

Not mentioned in the research study press release above, however, is the fact that the nutraceutical flavonol quercetin is abundant in certain human foods and — as does anakinra — reduces the activity of IL-1β and therefore significantly reduces arthritic inflammation and pain in both humans and lab animals. This anakinra-quercetin identicality of net biochemical effect towards arthritis raises the likelihood that dietary quercetin restores the health of the blood stem cells of aging animals, too.

As Erlund et al., 2000, summarize:

Flavonoids are a group of polyphenols widely occurring in plants. These compounds, especially the flavonol quercetin, exhibit a multitude of biological activities such as anticarcinogenic, antioxidative, and enzyme-modulating activities. Epidemiological studies indicate an inverse relationship between dietary intake of flavonoids (mainly quercetin) and cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Accordingly, experimentation with lab animals shows that quercetin can improve kidney health and function, lower blood pressure, ameliorate degeneration of intervertebral discs, accelerate growth of skin cells and the healing of wounds, reduce age-related development of inflammation-causing fat cells, and protect against osteoporosis. Both animal and human testing demonstrate that dietary rutin, converted to quercetin by bacteria in the lower alimentary canal, can materially reduce visceral and surface fat obesity, age-related and otherwise.

Probably tying all these effects together, however, is evidence that quercetin performs as a general senolytic agent, eliminating problematic, old dysfunctional cells from body tissues and thus eventually rectifying the downstream operations of various cellular and organ systems:

A fundamental aging mechanism that likely contributes to chronic diseases and age-related dysfunction is cellular senescence. Senescence refers to the essentially irreversible growth arrest that occurs when cells are subjected to potentially oncogenic insults. Even though senescent cell abundance in aging or diseased tissues is low, achieving a maximum of 15 percent of nucleated cells in very old primates, senescent cells can secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular matrix proteases, which together constitute the senescence-associated secretory phenotype or SASP. The SASP likely contributes to the correlation between senescent cell accumulation and local and systemic dysfunction and disease. Consistent with a role for cellular senescence in causing age-related dysfunction, clearing senescent cells by activating a drug-inducible ‘suicide’ gene enhances healthspan and delays multiple age-related phenotypes in genetically modified progeroid mice. Interestingly, despite only clearing 30 percent of the senescent cells, improvement in age-related phenotypes is profound. Thus, interventions that reduce the burden of senescent cells could ameliorate age-related disabilities and chronic diseases as a group.

Briefly hearkening back to the subject of an earlier post, it turns out that quercetin also slows down the dopamine-degrading activity of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) enzyme, possibly increasing the efficiency of operation of the human prefrontal cortex of those born with naturally faster-acting versions of the COMT gene – and, therefore, thereby possibly improving the effectiveness and soundness of discrimination and decision-making of the human majority.

Given that quercetin (unlike the arthritis medicine, anakinra) has long been part of the natural human diet, the question that naturally arises, then, is there any epidemiological evidence out there that a human diet providing especially high concentrations of this flavonoid imparts significant and unusual health and longevity benefits to the humans concerned?

Food Sources of Quercetin

The average daily quercetin intake in the European Union is 14 mg/day, while that of mainland Japanese citizens is 16 mg/day. In marked contrast to these two populations, average American daily consumption of quercetin is estimated as being 3.5 mg/day.

Quercetin is introduced into human bodies by way of two only slightly different chemical compounds found in food: quercetin itself, and rutin. Rutin is quercetin with an attached sugar (a disaccharide) molecule. Because of the quercetin concentration-diluting molecular presence of the sugar in rutin, it takes double the amount of rutin to provide an equivalent amount of quercetin.

Males note here that there is some small sample evidence that the male digestive system does not convert plant rutin into quercetin as effectively as does the female digestive system. Who knows? Perhaps this is an important reason for the generally lowered life expectancy of human males compared to females. See Erlund et al., again, for more detail.

Search and review of online data sources shows the following foods to contain the highest concentrations of quercetin and rutin:

Potential Epidemiological Evidence: Moving from the Anecdotal, to the Well-Documented, to the Poo-Poohed

A. The Officially Oldest Frenchwoman and Her Chocolate Habit

The Frenchwoman, Jeanne Calment, is documented as having inarguably lived for 122 years, 164 days. She idiosyncratically binged on a kilogram or so of chocolate a week. Assuming the chocolate she ate had the quercetin content of dark chocolate - containing 25 mg/100 g quercetin – Calment’s daily quercetin intake from chocolate alone would have averaged about 36 mg/day. This is about 10Xs the average daily quercetin intake of Americans, and about 2Xs that of the average Japanese or European.

B. Okinawa: the Land of the Immortals and the Sweet Potato

Okinawa’s Chinese neighbors on the west across the Chinese Sea are said to have, centuries ago, referred to the Okinawan islands as the “Land of the Immortals” because of the remarkable longevity of its inhabitants. Suzuki, Willcox, and Willcox (2017) write much more recently of these same people:1

We know from human epidemiological comparisons that some populations, such as the Japanese and, in particular, the Okinawans, who inhabit the most southwestern prefecture of Japan, have high active (“healthy” or “disability-free”) life expectancy – a measure of healthy aging. Japan is ranked first in active life expectancy, according to the World Health Organization, and Okinawa leads the Japanese rankings. Despite being the poorest prefecture in Japan, Okinawa has long been among the healthiest and longest lived. As a result, Okinawa has long had among the highest prevalence of centenarians in Japan and the world.

…Other studies involving the OCS [Okinawa Centenarian Study] dataset and/or the OCS team found healthier blood chemistry and hematology, younger hormonal patterns, higher bone density, and better cognitive function than age-matched counterparts in mainland Japan or the USA.

Average overall health of the Okinawan elderly population with regard to the diseases associated with aging is illustrated in the (2007) graph below.

The average quercetin daily intake of Okinawans, at the time of a 1950s dietary study, was about 1330 mg/day quercetin. This “especially high” daily input of quercetin in the (now disappearing) traditional diet of adult Okinawans is a result of the geographic location of the Okinawan islands – and a happenstance onetime cultural transfer from China:2

Historical records indicate that in 1605 an Okinawan man named Sokan Noguni brought a sweet potato seedling back from Fujian, a neighboring Chinese province with close cultural ties to Okinawa, and began growing it in his garden. Over the years he shared seeds with his neighbors and taught his friend, Gima Shinjo, how to raise this amazing new plant. Before long, Mr. Shinjo was enthusiastically spreading it among other people on the Okinawa islands.

In those days, there were about four strong typhoons every year, and rice paddies were often completely destroyed, exposing people to potential famine. But the hardy imo [sweet potato], buried deeper in the ground and better protected, held on and prospered despite the fierce storms and floods that hit the islands of Okinawa in the summertime. (Okinawa is smack in the middle of what is known as “hurricane alley”.) This strange and wonderful sweet potato proved to be a literal life saver to the Okinawans. It was largely due to the imo, and the stable source of calories it provided, that the population of Okinawa grew from 120,000 to 200,000 in the first decades of the 1600s.

About 67% of the weight (849 grams) of the average daily 1262 gram (1785 calories) traditional diet of Okinawans was made up by sweet potato in the 1950s. With a dry daily weight of 195 grams sweet potato consumption, and an average quercetin concentration of 0.68% by dry weight, records indicate the average Okinawan historically consumed about 1330 mg of quercetin per day – 83 times that of the average mainland Japanese, and 380 times that of the average American.

Interestingly, Willcox et al., 2007, interpret the high plasma DHEA levels found in Okinawans still eating a sweet potato-based diet in 1988 as somewhat direct evidence – an index of sort -- of the healthily-slow biological aging of these people. The authors hypothesize that these high DHEA blood plasma values are a result of the very mild chronic calorie restriction that makes up part of the traditional Okinawan eating culture. It’s clear, however, from a more recent report (2020) that sweet potatoes are not only a source of senolytic quercetin, but also constitute a very rich dietary source of DHEA.

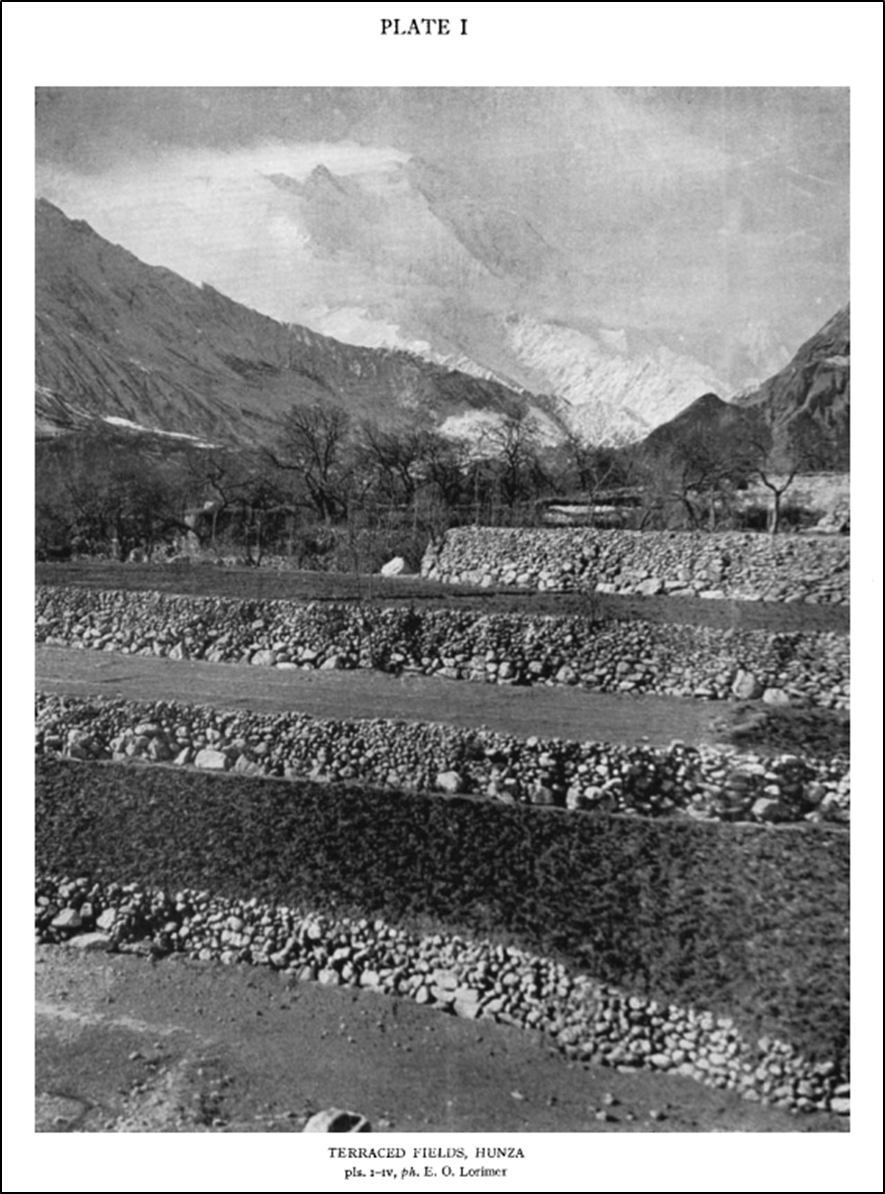

C. The Burusho (Hunza) and their “Detested” Bitter Buckwheat

While the birth and death records of Okinawa are unimpeachable, these were at least previously lacking in the very small high mountain state of Hunza, Gilgit, in now northeastern Pakistan. Nevertheless, based on memory, Burusho residents there claimed ages of 100 quite commonly, and occasionally 150-160.

Reportedly in 1983, for example (machine-translated from Bulgarian):

There was a case when one of the Hunzakuts, whose name was Said Abdul Mobudu, who arrived at the London Heathrow Airport, confused the employees of the immigration service when he presented his passport. According to the document, the Hunzakut was born in 1823 and he had turned 160 years old. The Mullah accompanying Mobudu noted that his ward is considered a saint in the country of Hunza, which is famous for its longevity. Mobudu has excellent health and common sense. He perfectly remembers events starting in 1850.

E.O. Lorimer (1938) writes:

The major crops grown by the Hunza people for their own use are wheat, barley, several kinds of millet, sweet and bitter buckwheat, nowadays also the highly-valued potato (introduced by the British in 1892) and small quantities of various pulses. Barley must have been the original staple crop, for all the traditional festivals, the Seed-sowing of early spring, the First Reaping of early summer and the Harvest Home, related to barley alone. The peasant is wise about rotation of crops and the various types of wheat, millet, etc., which thrive best in given conditions. Wheaten bread is much preferred to any other, but barley remains the largest crop because spring-sown barley ripens three or four weeks before even the winter-sown wheat, and the vacant fields can be resown with millet; whereas after the wheat only buckwheat can hope to ripen before winter. Bitter buckwheat is frankly detested, but it is hardier than the sweet and can better withstand an attack of an early frost, so a certain amount of it is always sown as an insurance.

Further, according to Lorimer:

Despite all diligence in tilling the ungrateful soil, despite the utmost care in rationing the year’s supply (rationing begins the moment the first barley crop is harvested), scarcely a household we knew was [not] out of flour and out of potatoes weeks before the first barley was ripe, and was living solely on turnip tops, greens and edible weeds.

These two passages from Lorimer indicate the “frankly detested” bitter buckwheat was necessarily consumed by the Burusho each year in late winter and/or early spring.

Assuming an adult daily consumption of 300 grams (1231 calories) of bitter/tartary buckwheat flour at the end of each winter and into the spring (this is equivalent to the daily calories provided by average daily Okinawan sweet potato consumption), daily quercetin-equivalents in the Hunza Valley would have been about 2500 mg –- 716 times the average American daily intake of the flavonoid, and very close to double that of the sweet potato-eating Okinawans.

Discussion

Each of the long-lived and healthily-aged historical human examples provided above ingested considerably more than ordinary amounts of quercetin and/or rutin during the course of their lifetimes. This fact may at least partially explain their long life- and health-spans. As remarked already, recent scientific research has shown that these plant polyphenols renovate aging cellular and tissue function, and therefore materially improve and sustain overall health.

Nevertheless, confounding this picture is the fact that both the Okinawans and the Burusho/Hunza spent a portion of each year under conditions of mild to moderate caloric restriction. Although it has not yet been at all conclusively demonstrated to be so for primates, caloric restriction has been shown to substantially increase the longevity of certain other (much smaller) organisms.

Note that Okinawans chronically consumed anomalous amounts quercetin (and DHEA) from their sweet potato-based diet. In contrast, it appears that the Burusho only took in extreme amounts of quercetin for short stretches of time at the end of each winter and into the spring. However, very recent research shows that occasional but acutely high oral intake of senolytic compounds is quite effective in significantly correcting the cellular effects of aging in the mouse:

An important observation is that senolytics appear to alleviate multiple types of dysfunction. The senolytic agents used here enhanced cardiac and vascular function in aging mice, reduced dysfunction caused by localized irradiation, and alleviated skeletal and neurological phenotypes in progeroid mice. Remarkably, in some cases, these drugs did so with only a single course of treatment. [Emphasis added.] In previous work, we and our collaborators found that genetic clearance of senescent cells slowed development of lordokyphosis, cataracts, and lipodystrophy in progeroid mice. Thus, the accumulation of senescent cells in association with a number of diseases, disabilities, and chronological aging likely contribute to the causation and pathophysiology of these problems or their symptoms. Together with chronic, ‘sterile’ inflammation, macromolecular dysfunction, and stem and progenitor cell dysfunction, cellular senescence may contribute to both aging phenotypes and increased susceptibility to a range of chronic diseases.

In judging the import and significance of the above provided epidemiological cases of accidental quercetin self-medication, it is worth noting here that the Mayo Clinic-hosted research group currently conducting most of the research using quercetin as a senolytic has already conducted some small clinical trials involving the flavanol, with positive results. See, for two examples, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7405395/ and https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31542391/.

Suzuki,M., Willcox, D.C., and Willcox, Bradley, 2017, Okinawa Centenarian Study – investigating aging among the world’s longest-lived people: in Encyclopedia of Geropsychology, Nancy A. Pachana, editor: Springer, 2608 pages.

Willcox, B.J., Willcox, D.C., and Suzuki, Makato, 2001, The Okinawa Program: Three Rivers Press, New York, 484 pages.